From: Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History by Stephen Jay Gould

🎞️ 1. When Pictures Tell Bigger Lies

Stephen Jay Gould begins his classic with a powerful idea: the pictures we draw of evolution shape how we think about it. Textbooks often show an evolutionary ladder—simple creatures giving way to more complex ones, with humans triumphantly perched at the top. This “iconography of expectation” reflects a bias toward progress. But nature, as Gould shows us, never agreed to that plotline.

👁️ 2. Enter Opabinia: The Star of the Prologue

Meet Opabinia: five eyes, a backward-facing mouth, and a long proboscis with a claw. Found in the Burgess Shale, this surreal creature is an evolutionary wild card. Gould uses it not only to captivate but to challenge assumptions. This was not a “failed experiment”—it was simply one of evolution’s many roads, most of which didn’t lead to us.

📊 3. The Shape of Evolution: Not a Ladder, but a Cone

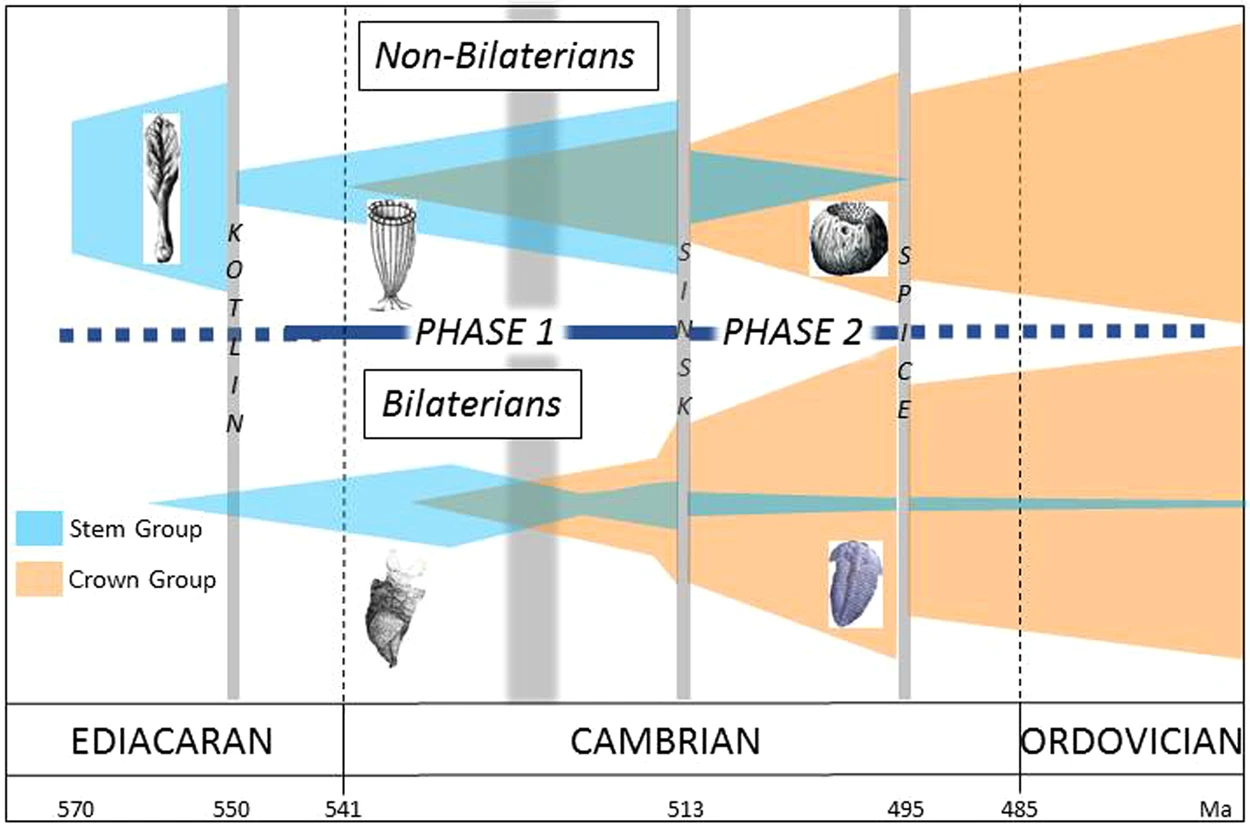

Zhuravlev, A.Y., Wood, R.A. The two phases of the Cambrian Explosion. Sci Rep 8, 16656 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34962-y

Zhuravlev, A.Y., Wood, R.A. The two phases of the Cambrian Explosion. Sci Rep 8, 16656 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34962-y

Gould argues that rather than a ladder, we should imagine evolution as a cone. At the base, organisms radiate into wildly different forms. Only a few lineages survive, creating the illusion of steady progress. The Burgess Shale snapshot reveals not ancestors of modern phyla—but mostly extinct forms, evolutionary side-streets that never rejoined the highway.

🌍 4. A Cambrian Carnival: Experimental Life at Its Peak

During the Cambrian Explosion (~505 million years ago), evolution went wild. Body plans multiplied. Limbs, eyes, and exoskeletons burst into existence. The fossils of the Burgess Shale are like a snapshot of a mad design competition. Genetically, this implies early toolkits (like Hox genes) were being reused and repurposed at lightning speed.

🧬 5. Genomic Echoes of Opabinia

Though we can't sequence Opabinia's genome, genomics gives us hints about its logic:

- Stem-group heritage: Opabinia likely shared ancestral genes with early arthropods—perhaps early uses of Pax genes for eye development, or conserved motor neuron systems for its lobed limbs.

- De novo structures: The proboscis may reflect genes expressed in new spatial patterns—an example of regulatory innovation rather than new protein-coding genes.

- Lost complexity: Its lineage may have gone extinct, taking unique genes and regulatory networks with it—just as hundreds of gene families have blinked out across time.

📚 6. Rethinking Evolution Through Fossils and Genes

“History is a tale of massive disparity and merciless winnowing, not a steady climb toward us.” – Stephen Jay Gould

Gould’s visual prologue is not just dramatic—it’s transformative. He invites readers to think about life differently: not as a march of improvement, but as a series of experiments, most of which failed. Modern genomics echoes this. Genomes, like fossils, record contingency, surprise, and erasure. What survives is not what's best—just what was lucky enough to persist.

🧠 Final Thought

By beginning with Opabinia and a handful of strange images, Gould sets up one of the boldest arguments in evolutionary thinking. It's not the fossils that are weird—it’s our expectations. And through the lens of genomics, that weirdness makes even more sense.

Want to explore how modern gene networks reflect ancient body plans? Or how extinct lineages left ghostly traces in today's genomes? Stay tuned for deeper dives into Gould’s brilliant narrative!

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons)

No comments:

Post a Comment